- Mcneill Dysphagia Therapy Program Protocol free. software download

- Mcneill Dysphagia Therapy Program Certification

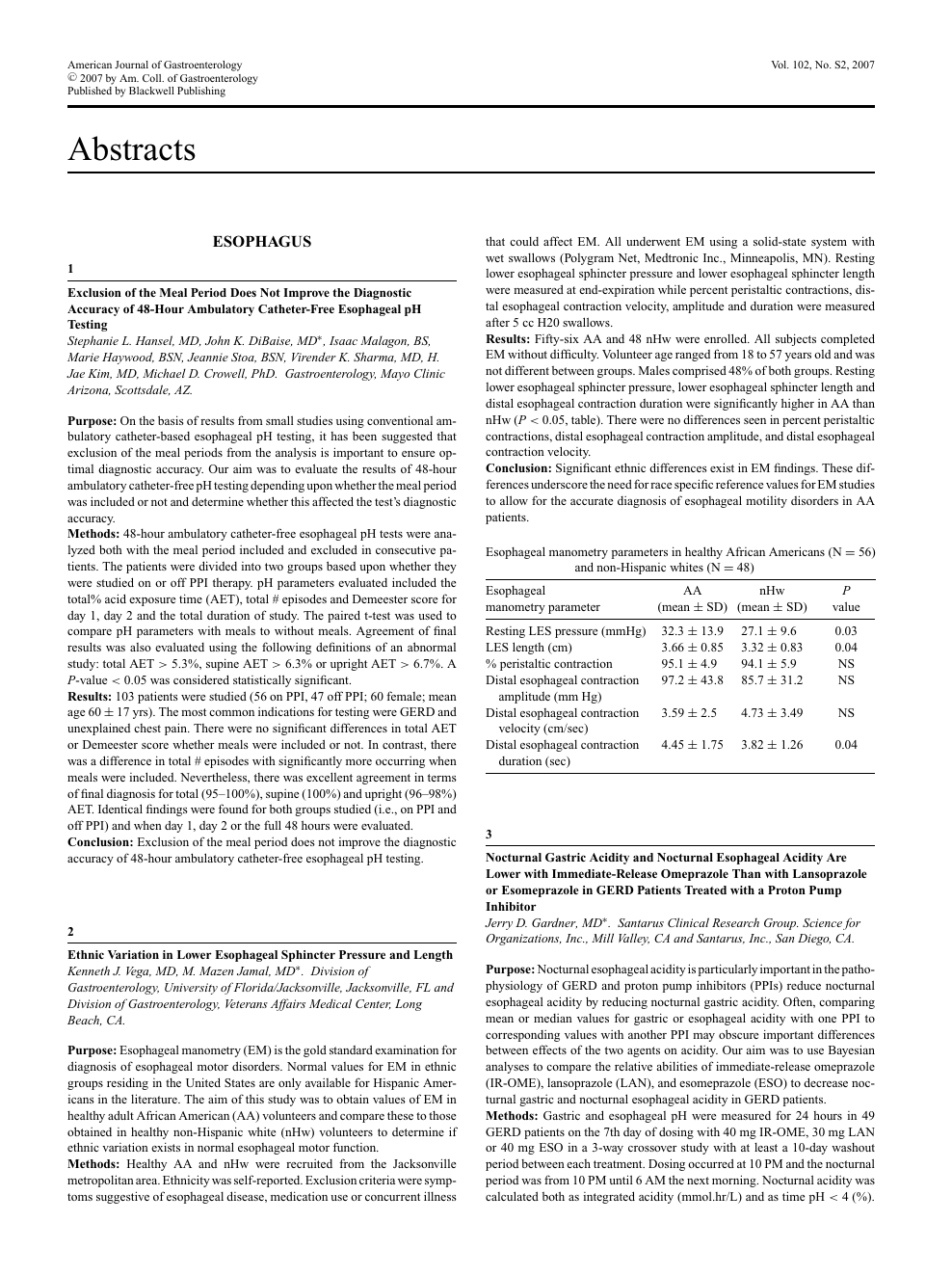

Mcneill dysphagia therapy program a case control study free sponsored downloads: therapy, parita suci data eye app Download parita suci buddha MP3 and Streaming parita suci buddha Music. Download And Listen Top parita suci buddha Songs, New MP3 parita suci buddha Hello from Africa!

Mcneill Dysphagia Therapy Program Protocol download free, software 01 22 Mcneill dysphagia therapy program a case control study free sponsored downloads: therapy, parita suci data eye app Download parita suci buddha MP3 and Streaming parita suci buddha Music. Sep 12, 2020. McNeill Dysphagia Tx Protocol (MDTP) 'Swallow hard and fast' - follows a dietary hierarchy with advancing steps of altered bolus volume (load) and consistency – Increased laryngeal and hyoid elevation, lingual-palatal pressures, FOIS, oral and pharyngeal temporal events (Crary et.

Dysphagia is a prevalent difficulty among aging adults. Though increasing age facilitates subtle physiologic changes in swallow function, age-related diseases are significant factors in the presence and severity of dysphagia. Among elderly diseases and health complications, stroke and dementia reflect high rates of dysphagia. In both conditions, dysphagia is associated with nutritional deficits and increased risk of pneumonia. Recent efforts have suggested that elderly community dwellers are also at risk for dysphagia and associated deficits in nutritional status and increased pneumonia risk. Swallowing rehabilitation is an effective approach to increase safe oral intake in these populations and recent research has demonstrated extended benefits related to improved nutritional status and reduced pneumonia rates.

In this manuscript, we review data describing age related changes in swallowing and discuss the relationship of dysphagia in patients following stroke, those with dementia, and in community dwelling elderly. Subsequently, we review basic approaches to dysphagia intervention including both compensatory and rehabilitative approaches. We conclude with a discussion on the positive impact of swallowing rehabilitation on malnutrition and pneumonia in elderly who either present with dysphagia or are at risk for dysphagia. Introduction Dysphagia (swallowing difficulty) is a growing health concern in our aging population. Age-related changes in swallowing physiology as well as age-related diseases are predisposing factors for dysphagia in the elderly. In the US, dysphagia affects 300,000–600,000 persons yearly.

Although the exact prevalence of dysphagia across different settings is unclear, conservative estimates suggest that 15% of the elderly population is affected by dysphagia. Furthermore, according to a single study, dysphagia referral rates among the elderly in a single tertiary teaching hospital increased 20% from 2002–2007; with 70% of referrals for persons above the age of 60.

The US Census Bureau indicates that in 2010, the population of persons above the age of 65 was 40 million. Taken together, this suggests that up to 6 million older adults could be considered at risk for dysphagia. Cool wolf games. Any disruption in the swallowing process may be defined as dysphagia. Persons with anatomical or physiologic deficits in the mouth, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus may demonstrate signs and symptoms of dysphagia.

In addition, dysphagia contributes to a variety of negative health status changes; most notably, increased risk of malnutrition and pneumonia. In this review, we will discuss how aging and disease impact swallowing physiology with a focus on nutritional status and pneumonia. We will conclude with a brief overview of dysphagia management approaches and consequences of dysphagia management on nutritional status and pneumonia in the elderly.

Aging effects on swallow function Swallow physiology changes with advancing age. Reductions in muscle mass and connective tissue elasticity result in loss of strength and range of motion. These age-related changes can negatively impact the effective and efficient flow of swallowed materials through the upper aerodigestive tract. In general, a subtle slowing of swallow processes occurs with advancing age. Oral preparation of food requires more time and material transits through the mechanism more slowly.

Over time, these subtle but cumulative changes can contribute to increased frequency of swallowed material penetrating into the upper airway and greater post-swallow residue during meals. Beyond subtle motor changes, age-related decrements in oral moisture, taste, and smell acuity may contribute to reduced swallowing performance in the elderly. Though sensorimotor changes related to healthy aging may contribute to voluntary alterations in dietary intake, the presence of age-related disease is the primary factor contributing to clinically significant dysphagia in the elderly. Conditions that may contribute to dysphagia Dysphagia affects up to 68% of elderly nursing home residents, up to 30% of elderly admitted to the hospital, up to 64% of patients after stroke, and 13%–38% of elderly who live independently.– Furthermore, dysphagia has been associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Two prevalent diseases of aging are stroke and dementia. In 2005, 2.6% of all noninstitutionalized adults (over 5 million people) in the US reported that they had previously experienced a stroke.

The prevalence of stroke also increases with age, with 8.1% of people older than 65 years reporting having a stroke. Similarly, adults older than 65 years demonstrate an increased prevalence of dementia, with estimates between 6%–14%., Prevalence of dementia increases to over 30% beyond 85 years of age, and over 37% beyond 90 years.

Common complications of dysphagia in both stroke and dementia include malnutrition and pneumonia. Dysphagia and nutrition in stroke Dysphagia is highly prevalent following stroke with estimates ranging 30%–65%., Specific to the US, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates that about 300,000–600,000 persons experience dysphagia as a result of stroke or other neurological deficits. Although many patients regain functional swallowing spontaneously within the first month following stroke, some patients maintain difficulty swallowing beyond 6 months., Complications that have been associated with dysphagia post-stroke include pneumonia, malnutrition, dehydration, poorer long-term outcome, increased length of hospital stay, increased rehabilitation time and the need for long-term care assistance, increased mortality, and increased health care costs. These complications impact the physical and social well being of patients, quality of life of both patients and caregivers, and the utilization of health care resources.

In the acute phase of stroke, between 40%–60% of patients are reported to have swallowing difficulties., These difficulties may contribute to malnutrition due to limited food and liquid intake. Decreased food and liquid intake may reflect altered level of consciousness, physical weakness, or incoordination in the swallowing mechanism. Although the odds of malnutrition are increased in the presence of dysphagia following stroke, pre-stroke factors should be considered when assessing nutritional status and predicting stroke outcome.

For example, upon admission, approximately 16% of stroke patients present with nutritional deficits. Dolby digital plus advanced audio driver windows 10. During acute hospitalization, nutritional deficits may worsen with reported prevalence increasing to 22%–26% at discharge from acute care.– Although nutritional deficits and dysphagia often coexist, malnutrition does not appear to be associated with dysphagia in the acute phase of stroke.

Rather, malnutrition is more prevalent during the post acute rehabilitation phase, with a reported prevalence of up to 45%. Reduced food/liquid intake during acute hospitalization associated with dysphagia may be a contributing factor to increased malnutrition rates during subsequent rehabilitation.

Dysphagia and pneumonia in stroke Post-stroke pneumonia is a common adverse infection that affects up to one-third of acute stroke patients., Pneumonia is also a leading cause of mortality after stroke, accounting for nearly 35% of post-stroke deaths. Most stroke-related pneumonias are believed to result from dysphagia and the subsequent aspiration of oropharyngeal material. Aspiration is defined as entry of food or liquid into the airway below the level of the true vocal cords, and aspiration pneumonia is defined as entrance of swallowed materials into the airway that results in lung infection. A recent systematic review reported that stroke patients with dysphagia demonstrate ≥3-fold increase in pneumonia risk with an 11-fold increase in pneumonia risk among patients with confirmed aspiration.

Mcneill Dysphagia Therapy Program Protocol free. software download

Along with this increased risk, the burden of aspiration pneumonia is high. Increased costs associated with longer hospitalization, greater disability at 3 and 6 months, and poor nutritional status during hospitalization characterize aspiration pneumonia in stroke. Dysphagia and dementia Dysphagia is a common symptom in dementia. It has been estimated that up to 45% of patients institutionalized with dementia have some degree of swallowing difficulty.

Different clinical presentations of dementia will result in different swallowing or feeding impairments.– Most commonly, patients with dementia demonstrate a slowing of the swallowing process. Slowed swallow processes may increase time taken to finish a meal and subsequently increase the risk for poor nutritional status.

Furthermore, patients with dementia often have difficulties self-feeding. These difficulties may relate to cognitive impairment, motor deficits such as weakness or apraxia, loss of appetite, and/or food avoidance. As a result, patients with dementia may experience weight loss and increased dependency for feeding. Subsequently, increased feeding dependency may lead to other dysphagia-related health problems, including pneumonia.

Weight loss can reflect decreased nutritional status which increases the patient's risk of opportunistic infections such as pneumonia.– Pneumonia is a common cause of mortality in patients with dementia. Thus, dementia, dysphagia, and related feeding impairments can lead to nutritional deficits which in turn contribute to pneumonia and mortality. Among elderly patients in particular, the presence of dementia is associated with higher hospital admission rates and overall higher mortality. Moreover, elderly patients admitted to a hospital with dementia have a higher overall prevalence of both pneumonia and stroke, suggesting that aging significantly increases the risk for these negative health states. Dysphagia and nutrition in community dwelling elderly adults Dysphagia can result in reduced or altered oral intake of food/liquid which, in turn, can contribute to lowered nutritional status. Casino roulette online. One group which merits more attention in reference to potential relationships between dysphagia and nutritional status is community dwelling elderly adults. Dysphagia can contribute to malnutrition, and malnutrition can further contribute to decreased functional capacity.

Thus, dysphagia may trigger or promote the frailty process among elderly persons. In a group of 65–94-year-old community dwelling adults, prevalence of dysphagia was reported to be 37.6%. Of these, 5.2% reported the use of a feeding tube at some point in life, and 12.9% reported the use of nutritional supplements to reach an adequate daily caloric intake. In another cohort of independently living older persons, prevalent cases of malnutrition or those at risk for malnutrition were estimated at 18.6% of elderly adults with dysphagia, and 12.3% of adults without dysphagia.

Significant differences in nutritional status were noted between these subgroups at 1-year follow-up. These figures underscore the prevalence and importance of malnutrition and dysphagia among elderly individuals. Moreover, they suggest that dysphagic elderly living in the community are likely to present with an elevated risk of malnutrition.

Dysphagia and pneumonia in community dwelling elderly adults The prevalence of community-acquired pneumonia in elderly adults is rising, with a greater risk of infection in those older than 75 years.– In addition, deaths from pneumonitis due to aspiration of solids and liquids (eg, aspiration pneumonia) are increasing and are currently ranked 15th on the CDC list of common causes of mortality. Frequency of pneumonia and its associated mortality increases with advancing age.

More specifically, the prevalence of pneumonia in community dwelling persons increases in a direct relationship to aging and the presence of disease. Furthermore, an increased prevalence of dysphagia in the elderly increases the risk for pneumonia. It appears that with the aging population, both dysphagia and pneumonia rates are increasing. However, relationships between dysphagia and pneumonia in community dwelling elderly are poorly understood. Cabre and colleagues reported that 55% of 134 community dwelling elderly adults 70 years and older diagnosed with pneumonia upon admission to a geriatric hospital unit, presented with clinical signs of oropharyngeal dysphagia. In this cohort, cases presenting with dysphagia were older, presented with more severe pneumonia, greater decline in functional status, and demonstrated a higher prevalence of malnutrition. These patients also demonstrated increased mortality at 30 days and 1-year follow-up.

Also, a recent study evaluated relationships between oropharyngeal dysphagia and the risk for malnutrition and lower respiratory tract infections-community–acquired pneumonia (LRTI-CAP) in a cohort of independently living older persons. Results indicated that 40% of LRTI-CAP cases presented with dysphagia, compared to 21.8% who did not present with dysphagia. These findings highlight the potential relationships among dysphagia, nutritional status, and pneumonia in community dwelling elderly. Dysphagia management The presence of a strong relationship between swallowing ability, nutritional status, and health outcomes in the elderly suggests a role for dysphagia management in this population. Successful swallowing interventions not only benefit individuals with reference to oral intake of food/liquid, but also have extended benefit to nutritional status and prevention of related morbidities such as pneumonia.

A variety of dysphagia management tools are available pending the characteristics of the swallowing impairment and the individual patient. Swallowing management Dysphagia management is a ‘team event'. Many professionals may contribute to the management of dysphagia symptoms in a given patient. Furthermore, no single strategy is appropriate for all elderly patients with dysphagia. Concerning behavioral management and therapy, speech-language pathologists (SLP) play a central role in the management of patients with dysphagia and related morbidities. SLP clinical assessment is often supplemented with imaging studies (endoscopy and/or fluoroscopy), and these professionals may engage in a wide range of interventions.

Some intervention strategies, termed ‘compensations', are intended to be utilized for short periods in patients who are anticipated to improve. Compensations are viewed as short-term adjustments to the patient, food and/or liquid, or environment, with the goal of maintaining nutrition and hydration needs until the patient can do so by themselves. Other patients require more direct, intense rehabilitation strategies to improve impaired swallow functions.

Common complications of dysphagia in both stroke and dementia include malnutrition and pneumonia. Dysphagia and nutrition in stroke Dysphagia is highly prevalent following stroke with estimates ranging 30%–65%., Specific to the US, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates that about 300,000–600,000 persons experience dysphagia as a result of stroke or other neurological deficits. Although many patients regain functional swallowing spontaneously within the first month following stroke, some patients maintain difficulty swallowing beyond 6 months., Complications that have been associated with dysphagia post-stroke include pneumonia, malnutrition, dehydration, poorer long-term outcome, increased length of hospital stay, increased rehabilitation time and the need for long-term care assistance, increased mortality, and increased health care costs. These complications impact the physical and social well being of patients, quality of life of both patients and caregivers, and the utilization of health care resources.

In the acute phase of stroke, between 40%–60% of patients are reported to have swallowing difficulties., These difficulties may contribute to malnutrition due to limited food and liquid intake. Decreased food and liquid intake may reflect altered level of consciousness, physical weakness, or incoordination in the swallowing mechanism. Although the odds of malnutrition are increased in the presence of dysphagia following stroke, pre-stroke factors should be considered when assessing nutritional status and predicting stroke outcome.

For example, upon admission, approximately 16% of stroke patients present with nutritional deficits. Dolby digital plus advanced audio driver windows 10. During acute hospitalization, nutritional deficits may worsen with reported prevalence increasing to 22%–26% at discharge from acute care.– Although nutritional deficits and dysphagia often coexist, malnutrition does not appear to be associated with dysphagia in the acute phase of stroke.

Rather, malnutrition is more prevalent during the post acute rehabilitation phase, with a reported prevalence of up to 45%. Reduced food/liquid intake during acute hospitalization associated with dysphagia may be a contributing factor to increased malnutrition rates during subsequent rehabilitation.

Dysphagia and pneumonia in stroke Post-stroke pneumonia is a common adverse infection that affects up to one-third of acute stroke patients., Pneumonia is also a leading cause of mortality after stroke, accounting for nearly 35% of post-stroke deaths. Most stroke-related pneumonias are believed to result from dysphagia and the subsequent aspiration of oropharyngeal material. Aspiration is defined as entry of food or liquid into the airway below the level of the true vocal cords, and aspiration pneumonia is defined as entrance of swallowed materials into the airway that results in lung infection. A recent systematic review reported that stroke patients with dysphagia demonstrate ≥3-fold increase in pneumonia risk with an 11-fold increase in pneumonia risk among patients with confirmed aspiration.

Mcneill Dysphagia Therapy Program Protocol free. software download

Along with this increased risk, the burden of aspiration pneumonia is high. Increased costs associated with longer hospitalization, greater disability at 3 and 6 months, and poor nutritional status during hospitalization characterize aspiration pneumonia in stroke. Dysphagia and dementia Dysphagia is a common symptom in dementia. It has been estimated that up to 45% of patients institutionalized with dementia have some degree of swallowing difficulty.

Different clinical presentations of dementia will result in different swallowing or feeding impairments.– Most commonly, patients with dementia demonstrate a slowing of the swallowing process. Slowed swallow processes may increase time taken to finish a meal and subsequently increase the risk for poor nutritional status.

Furthermore, patients with dementia often have difficulties self-feeding. These difficulties may relate to cognitive impairment, motor deficits such as weakness or apraxia, loss of appetite, and/or food avoidance. As a result, patients with dementia may experience weight loss and increased dependency for feeding. Subsequently, increased feeding dependency may lead to other dysphagia-related health problems, including pneumonia.

Weight loss can reflect decreased nutritional status which increases the patient's risk of opportunistic infections such as pneumonia.– Pneumonia is a common cause of mortality in patients with dementia. Thus, dementia, dysphagia, and related feeding impairments can lead to nutritional deficits which in turn contribute to pneumonia and mortality. Among elderly patients in particular, the presence of dementia is associated with higher hospital admission rates and overall higher mortality. Moreover, elderly patients admitted to a hospital with dementia have a higher overall prevalence of both pneumonia and stroke, suggesting that aging significantly increases the risk for these negative health states. Dysphagia and nutrition in community dwelling elderly adults Dysphagia can result in reduced or altered oral intake of food/liquid which, in turn, can contribute to lowered nutritional status. Casino roulette online. One group which merits more attention in reference to potential relationships between dysphagia and nutritional status is community dwelling elderly adults. Dysphagia can contribute to malnutrition, and malnutrition can further contribute to decreased functional capacity.

Thus, dysphagia may trigger or promote the frailty process among elderly persons. In a group of 65–94-year-old community dwelling adults, prevalence of dysphagia was reported to be 37.6%. Of these, 5.2% reported the use of a feeding tube at some point in life, and 12.9% reported the use of nutritional supplements to reach an adequate daily caloric intake. In another cohort of independently living older persons, prevalent cases of malnutrition or those at risk for malnutrition were estimated at 18.6% of elderly adults with dysphagia, and 12.3% of adults without dysphagia.

Significant differences in nutritional status were noted between these subgroups at 1-year follow-up. These figures underscore the prevalence and importance of malnutrition and dysphagia among elderly individuals. Moreover, they suggest that dysphagic elderly living in the community are likely to present with an elevated risk of malnutrition.

Dysphagia and pneumonia in community dwelling elderly adults The prevalence of community-acquired pneumonia in elderly adults is rising, with a greater risk of infection in those older than 75 years.– In addition, deaths from pneumonitis due to aspiration of solids and liquids (eg, aspiration pneumonia) are increasing and are currently ranked 15th on the CDC list of common causes of mortality. Frequency of pneumonia and its associated mortality increases with advancing age.

More specifically, the prevalence of pneumonia in community dwelling persons increases in a direct relationship to aging and the presence of disease. Furthermore, an increased prevalence of dysphagia in the elderly increases the risk for pneumonia. It appears that with the aging population, both dysphagia and pneumonia rates are increasing. However, relationships between dysphagia and pneumonia in community dwelling elderly are poorly understood. Cabre and colleagues reported that 55% of 134 community dwelling elderly adults 70 years and older diagnosed with pneumonia upon admission to a geriatric hospital unit, presented with clinical signs of oropharyngeal dysphagia. In this cohort, cases presenting with dysphagia were older, presented with more severe pneumonia, greater decline in functional status, and demonstrated a higher prevalence of malnutrition. These patients also demonstrated increased mortality at 30 days and 1-year follow-up.

Also, a recent study evaluated relationships between oropharyngeal dysphagia and the risk for malnutrition and lower respiratory tract infections-community–acquired pneumonia (LRTI-CAP) in a cohort of independently living older persons. Results indicated that 40% of LRTI-CAP cases presented with dysphagia, compared to 21.8% who did not present with dysphagia. These findings highlight the potential relationships among dysphagia, nutritional status, and pneumonia in community dwelling elderly. Dysphagia management The presence of a strong relationship between swallowing ability, nutritional status, and health outcomes in the elderly suggests a role for dysphagia management in this population. Successful swallowing interventions not only benefit individuals with reference to oral intake of food/liquid, but also have extended benefit to nutritional status and prevention of related morbidities such as pneumonia.

A variety of dysphagia management tools are available pending the characteristics of the swallowing impairment and the individual patient. Swallowing management Dysphagia management is a ‘team event'. Many professionals may contribute to the management of dysphagia symptoms in a given patient. Furthermore, no single strategy is appropriate for all elderly patients with dysphagia. Concerning behavioral management and therapy, speech-language pathologists (SLP) play a central role in the management of patients with dysphagia and related morbidities. SLP clinical assessment is often supplemented with imaging studies (endoscopy and/or fluoroscopy), and these professionals may engage in a wide range of interventions.

Some intervention strategies, termed ‘compensations', are intended to be utilized for short periods in patients who are anticipated to improve. Compensations are viewed as short-term adjustments to the patient, food and/or liquid, or environment, with the goal of maintaining nutrition and hydration needs until the patient can do so by themselves. Other patients require more direct, intense rehabilitation strategies to improve impaired swallow functions.

A brief review of each general strategy with examples follows. Compensatory management Compensatory strategies focus on implementation of techniques to facilitate continued safe oral intake of food and/or liquid; or to provide alternate sources of nutrition for maintenance of nutritional needs. Compensatory strategies are intended to have an immediate benefit on functional swallowing through simple adjustments that allow patients to continue oral diets safely. Compensatory strategies include, but are not limited to, postural adjustments of the patient, swallow maneuvers, and diet modifications (foods and/or liquids). Postural adjustments Changes in body and/or head posture may be recommended as compensatory techniques to reduce aspiration or residue. Changes in posture may alter the speed and flow direction of a food or liquid bolus, often with the intent of protecting the airway to facilitate a safe swallow. Lists commonly used postural adjustments.

In general, these postural adjustments are intended to be utilized short term, and the impact of each may be evaluated during the clinical examination or with imaging studies. Available literature on the benefit of these techniques is variable. For example, while some investigators report reduced aspiration from a chin down technique, others report no significant benefit or no superior benefit to other compensations like thick liquids. Furthermore, these compensatory strategies only impact nutritional status or pneumonia when they allow patients to consume adequate amounts of food/liquid in the absence of airway compromise leading to chest infection. No existing data confirms this potential benefit of postural adjustments and some data suggest that these strategies are inferior to more active rehabilitation efforts in the prevention of nutritional deficits and pneumonia.

Swallow maneuvers Swallow maneuvers are ‘abnormal' variants on the normal swallow intended to improve the safety or efficiency of swallow function. Various swallow maneuvers have been suggested to address different physiologic swallowing deficits. Presents commonly used swallow maneuvers.

Swallow maneuvers can be used as short-term compensations but many have also been used as swallow rehabilitative strategies. Different maneuvers are intended to address different aspects of the impaired swallow. For example, the supraglottic and super supraglottic swallow techniques both incorporate a voluntary breath hold and related laryngeal closure to protect the airway during swallowing. The Mendelsohn maneuver is intended to extend opening or more appropriately relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter. Bulk sms sender 2.8 crack. Finally, the effortful or ‘hard' swallow is intended to increase swallow forces on bolus materials with the result of less residue or airway compromise., Like postural adjustments, available data on the success of these techniques in patient populations is limited, conflicted, and often comprised of small samples.,– Thus, the best advice for clinicians is to verify the impact of these maneuvers using swallowing imaging studies before introducing any of them as compensatory strategies. Also, similar to postural adjustments, no significant research has demonstrated the impact of these maneuvers, when used as compensatory strategies, on nutritional status or pneumonia. Diet modifications: modification of foods/liquids Modifying the consistency of solid food and/or liquid is a mainstay of compensatory intervention for patients with dysphagia.

The goal of diet modification is to improve the safety and/or ease of oral consumption and thus maintain safe and adequate oral intake of food/liquid. However, low acceptability and resulting poor adherence with modified foods/liquids can contribute to increased risk of inadequate nutrition in elderly patients with dysphagia. Thickened liquids The use of thickened liquids is ‘one of the most frequently used compensatory interventions in hospitals and long-term care facilities'. Generally accepted clinical intuition and anecdotal evidence claim that thickened liquids have an effect in helping to control the speed, direction, duration, and clearance of the bolus. However, only scant evidence suggests that thickened liquids result in significant positive health outcomes with regards to nutritional status or pneumonia. Despite the overall lack of evidence supporting the use of thickened liquids, this strategy continues to be a cornerstone in dysphagia management in many facilities. For example, a survey of 145 SLPs by Garcia et al reported that 84.8% of the respondents felt that thickening liquids was an effective management strategy for swallowing disorders with nectar thick liquids being the most frequently used.

Unfortunately, the perceptions of these clinicians are not supported by available research. For example, Logemann et al reported that honey thick liquid was more effective in reducing aspiration during fluoroscopic swallow examination than nectar thick liquids (or the chin down technique). But, even this benefit disappeared when honey thick liquids were administered at the end of the examination.

Kuhlemeier et al identified ‘ultrathick' liquid to have lower aspiration rates than thick or thin liquids, although the manner of presentation (cup vs spoon) modified their results. Thus, available evidence appears discrepant from clinician perceptions regarding use of thick liquids.

Beyond this scenario, thick liquids may present pragmatic limitations in clinical practice. Limitations of thickened liquids A primary concern with the overuse of thickened liquids is the risk of dehydration in elderly patients with dysphagia. Patient compliance with thickened liquids is often reduced.

A recent survey of SLPs suggested that honey thick liquids were strongly disliked by their patients but even nectar thick liquids were poorly accepted by more than one in ten patients. Poor compliance with thickened liquids may lead to reduced fluid intake and an increased risk of dehydration. Beyond patient acceptance, no strong evidence is available supporting the use of thickened liquids as an intervention for patients with dysphagia. Only a single randomized trial has compared treatment outcomes between the chin down technique and nectar or honey thick liquids in patients with dysphagia. The results of this study revealed no significant differences between these strategies on the primary outcome of pneumonia. Consequently, strong evidence for the preferential use of liquid thickening as a strategy in dysphagia intervention is not currently available.

An alternative approach to thickened liquids has been recommended to counter the risk for dehydration due to reduced fluid intake and dislike for thickened liquids. This approach, the ‘Frazier water protocol', utilizes specific water intake guidelines and allows patients with dysphagia to consume water between meals. Although this technique has not yet been objectively assessed, experiences from the Frazier Rehabilitation Institute are impressive. Results suggest low rates of dehydration (2.1%) and chest infection (0.9%) in 234 elderly patients. With additional confirming results, this approach may become more widely used as a dysphagia intervention. Modified food diets Solid foods may be modified to accommodate perceived limitations in elderly patients with dysphagia.

Solid food modification has been suggested to promote safe swallowing and adequate nutrition. However, no strong and universal clinical guidelines are available to describe the most appropriate modification of foods. At least one study indicated that among nursing home residents, 91% of patients placed on modified diets were placed on overly restrictive diets. Only 5% of these patients were identified to be on an appropriate diet level matching their swallow ability and 4% of patients were placed on diets above their clinically measured swallow ability. More recently, in an attempt to standardize the application of modified diets in patients with dysphagia, the National Dysphagia Diet was proposed.

The National Dysphagia Diet is comprised of four levels of food modification with specific food items recommended at each level (). While this approach is commendable, unfortunately, to date no studies have compared the benefit of using this standardized approach to institution specific diet modification strategies.

Limitations of modified solids Although recommended to promote safe swallowing and reduce aspiration in patients with dysphagia, modified diets may result in reduced food intake, increasing the risk of malnutrition for some patients with dysphagia. Available literature on the nutritional benefit of modified diets is conflicted., One study evaluated dietary intake over the course of a day in hospitalized patients older than 60 years. The authors compared intake in patients consuming a regular diet to those consuming a texture modified diet and found that patients on the modified diet had a significantly lower nutritional intake in terms of energy and protein. Additionally, 54% of patients on a texture modified diet were recommended a nutritional supplement, compared with 24% of patients on a regular diet. Conversely, Germain et al compared patients consuming a modified diet with greater food choices to patients consuming a ‘standard' (more restricted) modified diet over a 12-week period. They found significantly greater nutritional intake in patients consuming the expanded option diet. Additionally, they observed a significant weight gain in the patients consuming the expanded option diet at the end of 12 weeks.

Feeding dependence and targeted feeding As mentioned previously, elderly patients with dementia and stroke may be dependent on others for feeding due to cognitive and/or physical limitations. Feeding dependence poses an increased risk for aspiration and related complications in patients with dysphagia due to factors such as rapid and uncontrolled presentation of food by feeders. This finding poses serious concern for patients with dysphagia on long-term modified diets. Implementing targeted feeding training can compensate for these difficulties and reduce related complications. For example, oral intake by targeted feeding (by trained individuals) in patients with dysphagia resulted in higher energy and protein intake compared to a control condition where no feeding assistance was provided.

In combination with specific training on feeding, other strategies to monitor rate and intake of food may help increase safety, decrease fatigue, and improve feedback on successful swallowing for the patients during the course of the meal. Eating in environments without external distractions, especially in skilled nursing or long-term care settings, are essential to this aim. Likewise, the prescription and provision of adaptive equipment like cups without rims and angled utensils, etc, may also support improved outcomes for elderly dysphagic patients. Provision of alternate nutrition Perhaps the ultimate form of compensation would be the use of alternate nutrition strategies. Non-oral feeding sources can benefit patients with nutritional deficits.

This is especially true in the elderly, as malnutrition contributes to a variety of health problems including cardiovascular disease, deterioration of cognitive status and immune system, and poorly healing pressure ulcers and wounds., Patient populations most commonly receiving non-oral feeding support include the general category of dysphagia (64.1%), and patients with stroke (65.1%) or dementia (30%). While non-oral feeding methods provide direct benefit in many clinical situations, they do not benefit all elderly patients with dysphagia or nutritional decline. For example, regarding enteral feeding in patients with advanced dementia, Finucane et al did not find strong evidence to suggest that non-oral feeding prevented aspiration pneumonia, prolonged survival, improved wound healing, or reduced infections. Moreover, a study of >80,000 Medicare beneficiaries over the age of 65 years indicated that presence of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube in hospitalized patients had a high mortality rate (23.1%).

Mcneill Dysphagia Therapy Program Certification

Mortality increased to 63% in 1 year. In addition, adverse events associated with non-oral feeding sources are common and include local wound complications, leakage around the insertion site, tube occlusion, and increased reflux leading to other complications such as pneumonia. Finally, the presence of alternate feeding methods can also promote a cascade of negative psychosocial features including depression and loss of social interaction associated with feeding. Fayol Principle In Hindi. , Despite the associated complications and impacts of non-oral feeding, provision of alternate feeding has demonstrated impact on nutritional adequacy and weight maintenance in some elderly populations and is therefore an important option in dysphagia management. Swallow rehabilitation The focus of swallow rehabilitation is to improve physiology of the impaired swallow. As such, many swallow rehabilitation approaches incorporate some form of exercise. Though the focus and amount of exercise varies widely from one rehabilitation approach to another, in general, exercise-based swallowing interventions have been shown to improve functional swallowing, minimize or prevent dysphagia-related morbidities, and improve impaired swallowing physiology.,– presents examples of recent exercise-based approaches to swallow rehabilitation. Though each of these programs differs in focus and technique, each shares some commonalities.

Specifically, each incorporates some component of resistance into the exercise program and each advocates an intensive therapy program monitored by the amount of work completed by patients. Some are specific to comprehensive swallow function, while others focus on strengthening individual swallow subsystems. Yet, each program is novel and shares the common goal of improving impaired swallowing physiology.

Examples of exercise-based swallow rehabilitation approaches Perhaps one of the more traditional approaches to swallow rehabilitation is the use of oral motor exercises. Although, there is limited information on the effectiveness of oral motor exercises, recent studies have shown effective strengthening of swallow musculature and hence improved swallowing with the use of lip and tongue resistance exercises., More recent exercise approaches such as expiratory muscle strength training (EMST) or the Shaker head lift exercise focus on the use of resistance to strengthen swallowing subsystems. As implied by the name, EMST attempts to strengthen the respiratory muscles of expiration.

However, initial research has indicated potential extended benefits to swallow function. For example, EMST has been shown to increase hyolaryngeal movement and improve airway protection in patients with Parkinson's disease. As indicated in the name, the head lift exercise developed by Shaker incorporates both repetitive and sustained head raises from a lying position. Improvements from this exercise include increased anterior laryngeal excursion and upper esophageal sphincter opening during swallowing, both of which contribute to more functional swallowing ability.

These positive physiologic changes have been demonstrated in healthy older adults and also in patients on tube feeding due to abnormal upper esophageal sphincter opening., The McNeill Dysphagia Therapy Program (MDTP) is an exercise-based therapy program, using swallowing as an exercise. From this perspective, MDTP addresses the entire swallow mechanism, not just subsystems as in other approaches.

This program is completed in daily sessions for 3 weeks and reports excellent functional improvement in patients with chronic dysphagia. In addition, recent studies have documented physiological improvements in strength, movement, and timing of the swallow., In addition to exercise-based interventions, the use of adjunctive modalities may be useful in swallowing rehabilitation. Application of adjunctive electrical stimulation has been widely debated and studied primarily in small samples. The rationale behind the application of electrical stimulation is that it facilitates increased muscle contraction during swallowing activity. Reported gains have included advances in oral diet, reduced aspiration, and reduced dependence on tube feeding., However, other studies have reported no significant differences in outcomes following dysphagia therapy with and without adjunctive neuromuscular electrical stimulation., Currently, the benefit of adding this modality to dyphagia therapy is not well documented; however, several smaller studies have suggested a clinical benefit. Surface electromyography (sEMG) has been demonstrated as a beneficial feedback mechanism in dysphagia rehabilitation.

SEMG biofeedback provides immediate information on neuromuscular activity associated with swallowing and is reported to help patients learn novel swallowing maneuvers quickly. Studies have documented that sEMG biofeedback facilitates favorable outcomes with reduced therapy time in patients, even with chronic dysphagia.–. Impact of swallow rehabilitation on nutritional status and pneumonia As presented above, dysphagia, nutritional status, and pneumonia appear to have strong interrelationships in various elderly populations. Recent evidence suggests that successful swallowing rehabilitation and/or early preventative efforts may reduce the frequency of both malnutrition and pneumonia in elderly patients with dysphagia. For example, patients with dysphagia in acute stroke who received an intensive exercise-based swallow rehabilitation program demonstrated less malnutrition and pneumonia compared to patients receiving diet modifications and compensations or those receiving no intervention. Other studies have demonstrated improved functional oral intake following successful swallow rehabilitation measured by the Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS), removal of PEG tube, and/or improved nutritional markers.,– In the head and neck cancer population, recent clinical research has shown that exercise during the course of chemoradiation treatment helps preserve muscle mass with reduced negative nutritional outcomes common in this population.

Finally, one exercise-based swallow rehabilitation program (MDTP) has demonstrated positive nutritional outcomes in patients with chronic dysphagia, including weight gain, removal of feeding tubes, and increased oral intake. These benefits were maintained at a 3-month follow-up evaluation., Collectively, such research suggests that intensive swallow rehabilitation can result in improved nutritional status and a reduction of pneumonia in a variety of elderly populations with dysphagia. Summary A strong relationship appears to exist between dysphagia and the negative health outcomes of malnutrition and pneumonia in patients following stroke, those with dementia, and also in community dwelling elderly adults. This trilogy of deficits, prominent among the elderly, demands more efforts focused on early identification and effective rehabilitation and prevention. Addressing issues such as the most efficient and effective methods to identify dysphagia and malnutrition in high-risk patients and community dwelling elderly adults could result in reduced morbidity in elderly populations. Of particular interest are recent studies that implicate benefit from intensive swallowing rehabilitation in preventing nutritional decline and pneumonia in adults with dysphagia.

Future research should extend this ‘prophylactic' approach to other at-risk populations including community dwelling elderly adults.